Summary of the House of Commons meeting on the rise of anti-Semitism in schools

Daniel Ben-Ami is a writer and journalist with an interest in the relationship between contemporary anti-Semitism and identity politics. We asked him to report back on an event to launch a new report from the Henry Jackson Society (HJS). We also asked Charlotte Littlewood, one of the speakers from the HJS, if she wished to respond. Her response is also published below. For DDU, their conversation raises some important questions, including whether it is helpful or not to respond to anti-Semitism by seeking special classification in the way of other BAME groups. If not, what might be a better response?

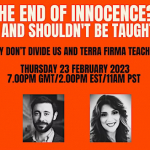

On 28 February the Henry Jackson Society (HJS), a think tank, organised a meeting at the House of Commons on the theme of the rise of anti-Semitism in schools.

The event was designed to publicise a report by Charlotte Littlewood, an HJS research fellow, showing a sharp rise in anti-Semitic incidents of pupil misconduct. The survey was based on 3,335 freedom of information requests sent out to all secondary schools and further education colleges in England. Responses were received from 1,314 schools.

At the meeting, Littlewood recommended that schools should implement the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) definition of anti-Semitism. This definition holds, among other things, that denying the state of Israel the right to exist is a form of anti-Semitism. She rejected the view that implementing this definition would have a chilling effect on free speech.

Dave Rich, the head of policy at the Community Security Trust (a charity that protects British Jews from anti-Semitism), put the results of the schools survey into a broader context of rising anti-Semitism. That includes different forms of anti-Semitism, such as that from the far right, far left and Islamist extremism. He pointed out that, although society is generally becoming less prone to racism, the trends in relation to anti-Semitism are moving in the opposite direction. Young people in particular are prone to believing conspiracy theories and these are in turn closely associated with anti-Semitism.

Devora Stoll, director for strategic partnerships with StandWithUs UK, a British charity educating about Israel, talked about her experience as a Teach First graduate teacher. She pointed out that anti-Semitism was often not treated as seriously as other forms of hate as Jews were often considered ‘white passing’.

The meeting was chaired by Gavin Williamson, a Conservative MP and former secretary of state for education. In his time as a minister he encouraged universities to adopt the IHRA definition of anti-Semitism.

Although the report suggested a worrying trend there are reasons to be wary of the approach generally favoured at the meeting:

- Imposing a particular definition of anti-Semitism raises problems both in practice and in principle. Anti-Semitism is a complex phenomenon that resists straightforward definition. It notoriously changes its form substantially over time. The imposition of a fixed definition, despite the protestations, also raises questions in relation to free speech.

- It blurs the difference between adults and children. Precisely because anti-Semitism is so complex there is a strong tendency to oversimplify it when teaching it in schools. For example, the connections often made between Anne Frank, who was eventually murdered by the Nazis, and school bullying. The idea is presumably to make Nazi persecution seem ‘relevant’ to school pupils, but it all too easily ends up relativising the experience of the Holocaust. There is no meaningful comparison between bullying, even in its most brutal form, and a genocidal drive to physically annihilate all Jews.

- Many of the complaints about anti-Semitism were made within the framework of identity politics. The demand was not to reject identity politics as inherently divisive but to classify Jews as part of the BAME (Black and Minority Ethnic) victim category.

Daniel Ben-Ami runs the Radicalism of Fools website on rethinking anti-Semitism.

Response from Charlotte Littlewood

Daniel Ben-Ami raises three concerns:

Imposing a particular definition of anti-Semitism, such as the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) definition, raises problems both in practice and in principle. Anti-Semitism is a complex phenomenon which resists straightforward definition. It notoriously changes its form substantially over time. The imposition of a fixed definition, despite the protestations, also raises questions in relation to free speech.

Antisemitism is an ancient hatred that has persistently seen Jews as the ‘other’ attaching to them connotations of untrustworthiness, greed and evil deeds. It is this hatred that drives the many ways in which this has manifested. Indeed, its manifestations change from swastikas and gas chambers to holding Jews accountable for Israel’s policies. But the underlying hatred, the ideas on which it is based, remains consistent. There is no other hatred that has so often turned to violence against the same group. As per the IHRA definition, I was relying on the findings of Rebecca Tuck KC in her independent review of antisemitism in the NUS, where she found that the IHRA definition did not have a chilling effect on criticism of Israel. You will find this on page 106 of her report.

It blurs the difference between adults and children. Precisely because anti-Semitism is so complex there is a strong tendency to oversimplify it when teaching it in schools. For example, the connections often made between Anne Frank, who was eventually murdered by the Nazis, and school bullying. The idea is presumably to make Nazi persecution seem “relevant” to school pupils but it all too easily ends up relativising the experience of the Holocaust. There is no meaningful comparison between bullying, even in its most brutal form, and a genocidal drive to physically annihilate all Jews.

I am not entirely sure what Daniel means here. But there is most certainly a connection between stereotyping and bigotry in the classroom and real-world discrimination. Bullying policy in schools and the Equalities Act are there to ensure equality and tolerance is fostered in schools for this very end. An interesting report that looks at religious education is useful here, the report by the Commission on Religious Education, found that a lack of adequate training and support for teachers has resulted in a religious education that is sometimes ‘reduced to crude differences between denominations’ and can sometimes ‘inadvertently reinforce stereotypes about religions rather than challenge them’.

We are actually calling for a less-reductive approach to teaching. Emphatically, we call for teaching to go beyond the Holocaust and teach how anti-Semitism is an ancient hate, the Holocaust being just one violent manifestation of many and that that hate persists to this day.

Many of the complaints about anti-Semitism were made within the framework of identity politics. The demand was not to reject identity politics as inherently divisive but to classify Jews as part of the BAME (Black and Minority Ethnic) victim category.

I agree there was a keen interest in this from the audience. The answer from all three panellists centred on how Jews were not viewed as a discriminated minority in the same way those who are considered BAME are.