‘Diversity & Anti-Racism’ and the threat to education in schools

On 24 July 2024, DDU sent an open letter to The Key – signed by a combination of scholars, teachers and parents – detailing our concerns about their Anti-Racism Curriculum Review which, knowingly or not, embeds significant precepts from critical race theory. In our view, these precepts are detrimental to educational goals and lack popular consent.

In their response The Key pointed out the following:

- The reference to Nazi Germany has been removed (which it has been)

- The protected characteristics were in respect to lesson-plan content not pupils

- They do not see themselves as promoting anti-British content.

Below you can read our original letter followed by our statement which addresses their second and third points.

Original Open Letter from DDU sent to The Key on 24 July 2024

Dear Chris Kenyon (CEO) and Michael McGarvey (MD),

The Key’s recent Anti-Racism Curriculum Review (Secondary) has chosen the categories of anti-racism and inclusivity as the predominant lens with which to review, and reframe, all existing curriculum subjects. No reasons are given for this choice. While we can easily assume a consensus that racism is abhorrent, we don’t think there is a consensus that schools and the curriculum are suitable places to solve political problems like racism. Reasonable people will have different views about the relationship between politics, racism and education, but because no reasons are given for the review, it sounds like an unjustified imposition. We would like to draw your attention to the following objections to the section on History in particular because, along with English, it is often the subject of wider controversy.

The books you recommend (Olusoga and Tharoor) are decidedly partisan in their historiographical approach and it is surprising to see an organisation of your size and influence endorse them uncritically, and with no reference to historians with opposing historical approaches. When teaching History, lack of due diligence over such matters deprives pupils of the chance to develop nuance and depth of thinking. School education, including the curriculum, comes under the jurisdiction of Sections 406 & 407 of the Education Act, which require upholding the principle of impartiality. Your section on History shows no recognition of this. While the possibility and desirability of impartiality in general are not settled in educational philosophy, in a multi-ethnic, multi-religious society like Britain, institutional impartiality is even more important, however difficult.

But your review effectively gives a green light to those for whom the very idea of impartiality is clearly anathema. For example, one of the suggestions is to avoid ‘the balance sheet model’ when teaching about Britain’s Empire because in this model ‘the beneficiaries of Empire were one group of people (i.e. the colonizers) and the losers were those who were colonized.’ (p.3). The review’s alternative is that the British Empire should be taught as if it were like any other ‘global power that committed atrocities, e.g. Nazi Germany’. This is historically and educationally illiterate, and morally relativistic to the point of being unethical.

Pupils who go to British schools need to learn about the history of important political and social events that have contributed to modern Britain, irrespective of pupils’ ethnicity, and asking such questions, weighing up the credibility of answers, giving and asking for reasons (‘the balance sheet model’) is a crucially important part of pedagogy in History teaching, and most other Humanities subjects. Applying Diversity as a supervening curricular principle for the curriculum weakens the subject knowledge: this is evident from nonsensical statements such as ‘The past is diverse’. Restricting and/or reframing curriculum knowledge content according to a political principle, i.e. Diversity, is a de facto denial that education has any value in its own right. This exacerbates an already deleterious level of instrumentalisation of schools and curriculum, and does not sit well with the professional reputation The Key has for its other school services.

We appreciate this initiative may have been undertaken out of a desire to do good, but it is clear that little or no thought has been given to unintended consequences. For example, far from encouraging a welcoming inclusive ethos, asking teachers to consider adding a box for protected characteristics on their lesson plans suggests pupils can be fundamentally divided according to protected characteristics, which are presented as more important than their commonality, including their country in common, Britain. At a time when social solidarity is under considerable strain for various reasons, actively promoting anti-patriotic beliefs makes it more difficult for our younger generation to form bonds that are substantively inclusive – based on equality as national citizens.

Instead, the Review offers a weak form of inclusivity by tick-box that actually endorses inequality according to ethnicity. While most parents would be happy for teachers to teach about Britain’s history – the inspiring and the reprehensible – we do not think they would be happy for their children to be taught to be ashamed or guilty about their country’s past, which is the implicit message of the section on History in your Review. Schools are not mandated to indoctrinate against their society’s prevailing socio-cultural beliefs.

In the interests of transparency and maintaining public trust, we hope you will consider the following questions:

- What is the evidence of racism in schools that merits this review?

- What evidence do you have that the curriculum has a causal effect on racism?

- Who have you consulted for this review?

- Who has approved this review for publication?

- Have you considered alternative arguments to this Critical Social Justice informed approach (one adopted by the third-party organisation you recommend, The Black Curriculum), and if so, what are your reasons for rejecting, or not acknowledging, opposing views?

We look forward to hearing your response.

Best Wishes,

Signatories

DDU Advisory Council:

Alka Sehgal Cuthbert

Tim Luckhurst

Carole Sherwood

Hardeep Singh

Khadija Khan

George Owers

Tarjinder Gill (primary teacher)

Mark McConnell (secondary teacher)

Josephine Hussey (primary teacher)

Brian Eastty (teacher)

Louise Fahey

Professor David Abulafia CBE FBA, Cambridge University

Professor Anna Sapir Abulafia FBA, Oxford University

Nigel Biggar Regius Professor Emeritus of Moral Theology & Senior Research Fellow, University of Oxford

Professor Robert Tombs

Dr Shirley Lawes (UCL, Institute of Education)

James Heartfield author of The British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society and Britain’s Empires 1600-2020

Kate Deeming (Scottish Union for Education, parents and supporters coordinator)

Dr Stuart Waiton (senior lecturer in Criminology, Abertay University)

Keith Jordan director of Our Duty

Cathy Mudge retired midwife/nurse, Protect Teach

Gilli Blick retired Protect Teach, parent & grandparent

Jenny Dingsdale Protect Teach

Dr Siobhan Spencer MBE Derbyshire Gypsy Liaison Group

Claire Orchard National Women & Children Safeguarding Group

Alison Wren retired science teacher, grandparent, governor

J. Shepherd, parent, grandparent, ex NHS worker. Dorset

M Barber, parent, Norwich

Leigh Taylor, primary school teacher & parent, Darlington

E. Evans, parent, Derby.

Paul Cormie, parent, former school governor, Manchester

E. Harewood, parent

R.Nicholls, social worker and parent

G. Murphy, Colchester, parent and official bloody nuisance

N. England, clinical scientist and concerned parent

DDU Statement: The Key’s Anti-Racism Curriculum Review – Ideological not Educational

The Key Supports Services Ltd is a company with an annual turnover of over £21million. It offers all manner of support services to school leaders, from template letters and Continuing Professional Development (CPD), to briefings on new government guidelines. It is used by over half of England’s schools and educational trusts and so has a de facto imprimatur over the way schools at a local level interpret official policies and legislation. The Key’s recent foray into anti-racism in schools is a cause for great concern for those who think schools should be: a) publicly accountable for decisions to promote or endorse ideas and practices in schools which lack public consent; and b) should be confining their ambitions to educating the young rather than using them for political social engineering.

The Key offers a reading list for staff, for example, that suggests to school leaders that they should ‘help your team develop an understanding of racism, anti-racism, white privilege and unconscious bias’. Unfortunately, being a business, much of The Key’s content is only available for paid-up members. It states that ‘some of this reading will present opposing views’, but this is not evident from the books that are publicly visible. Ibram X Kendi, Akala, Nikesh Shukla, Renni Eddo-Lodge and Ijeoma Oluo are American and British writers who hold a particular view of their societies as systemically racist and a particular view of history in which past racism can never be overcome.

One poll suggests that this deeply pessimistic view of British society, held by an elite cultural minority, is not necessarily shared by the majority of British citizens. The main aim of the reading list, and The Key’s Anti-Racism Curriculum Review, seems to be that teachers need ‘to understand the issues’, but neither the issues nor the reasons why they are singled out for special attention in the school curriculum are explicit.

The Key does not suggest that school leaders provide, for example, opportunities for teachers to learn more about the history of Britain so they can deal with sensitive topics with more confidence and educational objectivity. This would entail learning about Britain’s role in the slave trade, something which it had in common with many other countries, and Britain’s unique role in ending slavery and inspiring others, Frederick Douglass for example, in their struggle for greater freedom. This would be an educationally objective and responsible approach in keeping with Britain’s broadly liberal educational tradition.

In contrast, the reading list and Anti-Racist Curriculum Review appear to be an unthinking exercise in legitimising celebrations of vaguely defined Diversity. Most have little or no problem with diversity in fact (i.e. living in multi-ethnic areas), but Diversity capitalised is a political project that seeks to change Britain’s culture, and social relationships, through educational and cultural institutions rather than through established political activity. Not everyone may wish to celebrate Diversity, and they may have good reasons for their opinions. There is no evidence from The Key’s Review that they have even thought about these opposing, but widely-held views.

At the very least, we think there are fundamental questions that need to be discussed by anyone endorsing guidance that promotes a form of anti-racism that encourages the recognition and valorisation of ethnic differences over commonality:

- Is racism something schools should be tackling or is it something adults should be doing among themselves, as equal citizens, in the political sphere?

- Is there really such a thing as BAME history? Could using this category encourage British citizens to identify with ethnic rather than national identity? Could this approach encourage an unhelpful sectarianism rather than social cohesion?

- When you advise teachers that they should make sure that when covering Britain’s role in ending slavery, they should also talk about the fact that Britain ‘continued, if not stepped up, its colonisation activities across the globe’, is that gross generalisation intended to educate, or to encourage a negative moral evaluation of British history? By minimising the significance of Britain’s anti-slavery activities among both elite and popular sections of society, it suggests that the latter is more the intended objective.

You recommend The Black Curriculum as a legitimate resource for teachers. The company was founded by Lavinya Stennett, whose expertise and experience of education or working in schools is unclear, and whose motivation is educational activism and promoting a version of anti-racism based on critical race theory. There are good reasons why critical race theory is not a suitable basis for either the school curriculum or wider school practice. At its heart, the speculative theory embeds the idea of a society fundamentally divided by race. From this point, it posits rigid identities as non-white victims who are bearers of truth via lived experience, and white holders of privilege whose self-interpretations of their lived experience are tainted by historical sins. Traditional standards of disciplinary knowledge, with its standards of reliability and truth, invariably slip under emotive claims of ‘racial justice’.

Was any of this discussed and approved of by The Key’s board of directors? Who did seek and sanction The Key’s Anti-Racism Curriculum Review and its recommended reading list for teachers? To say (as they do in one of their responses to us) that the Review is only intended for teachers’ consumption and not for direct use in the classroom is highly disingenuous. School leaders pay for The Key’s services; they are unlikely to do so without the expectation that there will be some impact on what the teachers do in their lessons – whether that be in their selection, or framing, of content.

In endorsing this ideology, The Key opens the door to the vocal minority of activist teachers who do not believe in the value of impartiality or objectivity, which are enshrined in law. Similarly, to offer the defence that the suggestion to list protected characteristics is not intended to categorise pupils, but to be used by teachers when planning lessons, is not reassuring. In suggesting curriculum content be selected according to a legal-political category rather than any disciplinary criteria, educational aims become secondary to those of political/cultural change.

In short, The Key’s Anti-Racist Curriculum Review gives the green light to activists like Penny Rabiger, who formerly worked at The Key and is now at the Centre for Race, Education and Decoloniality at Leeds Beckett University, and advises teachers to see themselves as ‘circumventors of resistance’ who should ‘watch out for the impartiality police’ (presumably for a fee). The requirements that teachers strive to teach impartially and base lessons on objective knowledge are legal requirements as well as established good school practice in democratic societies. Rabiger does not explain why she thinks she, and teachers, should be exempted. The Key is hardly alone in participating in this attempt at cultural change, but it is one of the largest among a veritable new sector of third-party organisations in the educational landscape offering guidance based on alleged expertise in anti-racism.

The existence of companies like The Key, and the fact that many school leaders feel the need to pay for their services, is a big indictment of present and past governments, of both parties, to take education seriously. It represents an outsourcing of responsibility on the part of government, departmental and professional leaders, who need to decide whether Britain really is so racist that a wholesale review of the curriculum, through ‘the lens’ of anti-racism (or any other extra-epistemological lens) is justified. And if so, it needs to have the widest public conversations, draw up a national educational policy and put it to the public for our consent or rejection.

As it stands, British citizens are, in effect, paying for schools and teachers to be the conduit of a political ideology that is hostile to Britain’s culture and history. This is an abdication on the part of government, education institutions, including (or especially) teacher-training departments, professional bodies, education unions, exam boards and publishers. Instead of a collective endeavour to provide a public service of education for our young based on a curriculum created from the best knowledge to date, and taught with a view to opening minds, we are seeing more and more signs that schools and teachers are being used to legitimise a single political interpretation of race, racism and anti-racism. This is anti-democratic and anti-educational.

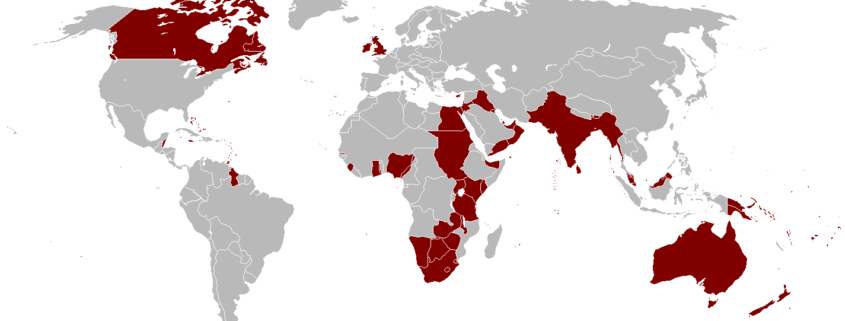

Image: British Empire in 1921, via Wikimedia Commons